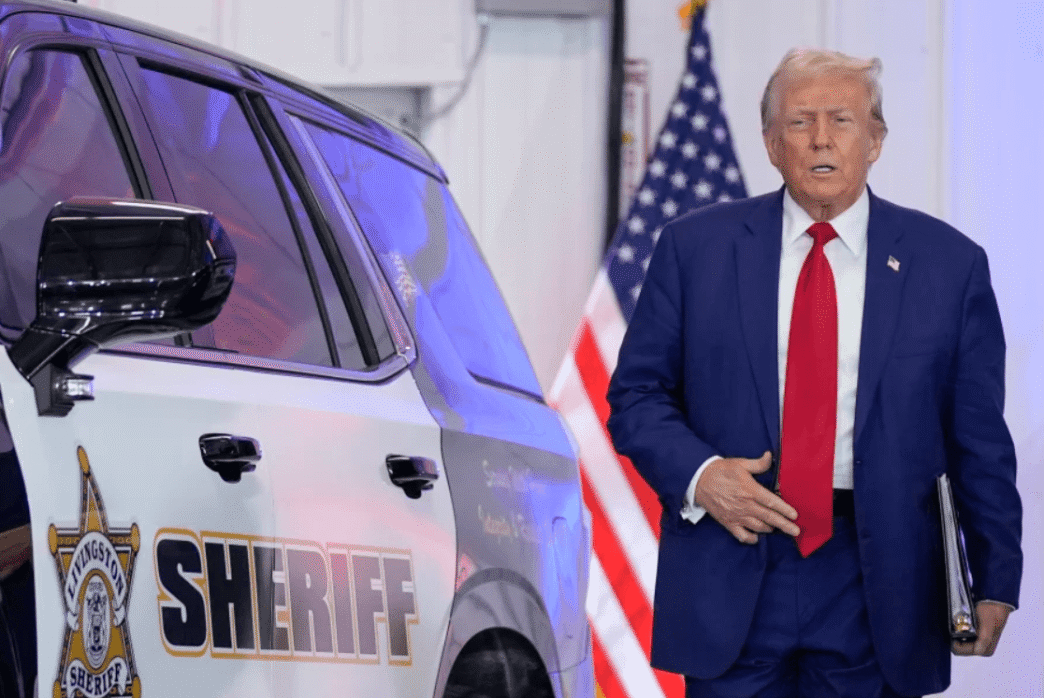

Former President Donald Trump has signed two executive orders aimed at strengthening local law enforcement and cracking down on cities and states that resist federal immigration enforcement. The orders reflect a broader White House agenda to deepen collaboration between local police and federal agencies.

The first executive order focuses on enhancing the capabilities of local police departments. It instructs federal agencies to support state and local police by developing updated best practices, improving officer training and compensation, and enhancing the collection and reporting of crime data—initiatives generally welcomed by law enforcement professionals.

Peter Moskos, a former officer and professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, sees value in these proposals. “These are definitely things the federal government can do to make communities safer,” said Moskos, author of Back From The Brink, which chronicles New York’s decline in crime during the 1990s.

However, Moskos is concerned about other parts of the order. One section, titled Holding State and Local Officials Accountable, directs the attorney general to pursue legal action against state and local leaders for civil rights violations related to DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion) programs, or for obstructing law enforcement officers in the line of duty.

“As a whole, it’s troubling,” Moskos said, citing the federal government’s aggressive approach to controlling local policing.

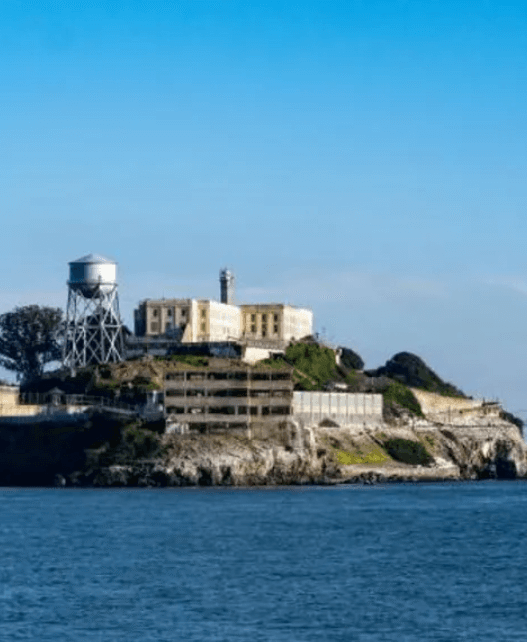

This concern over “obstruction” is echoed in a second executive order signed the same day, which directs the attorney general and secretary of homeland security to identify jurisdictions they believe are hindering federal immigration enforcement.

The move marks another escalation in the administration’s ongoing campaign against so-called “sanctuary” cities. Previously, such jurisdictions faced threats of funding cuts. Now, the administration is signaling a willingness to pursue legal action under federal law.

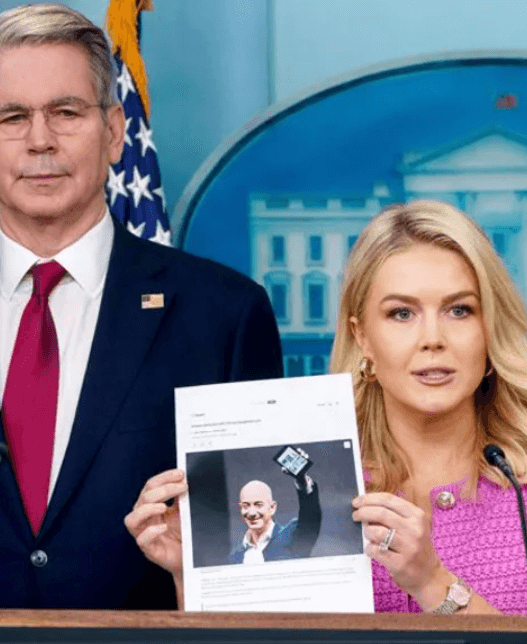

“It’s very simple,” said White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt. “Follow the law, respect the law, and don’t block federal immigration or law enforcement officials when they’re trying to remove public safety threats.”

Tensions heightened further when the FBI arrested Wisconsin Judge Hannah Dugan last Friday. She allegedly attempted to help a man evade ICE agents in her Milwaukee County courtroom.

“If you cross the line by harboring or concealing an illegal alien from ICE, you will be prosecuted—judge or not,” warned White House Border Czar Tom Homan at a press briefing.

These executive orders have raised questions among local law enforcement leaders about potential legal risks for not complying with ICE.

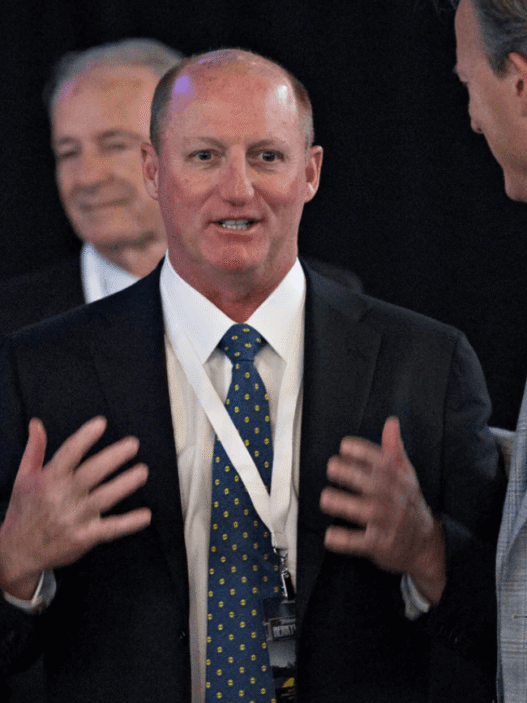

“I’ve never told anyone to interfere with federal authorities,” said Sheriff Paul Heroux of Bristol County, Massachusetts. But he emphasized that state law prohibits him from holding detainees past their court-ordered release dates for ICE. “I don’t see how an executive order can change that,” he said.

Heroux pointed to federal statute 287(g), which already allows local police to voluntarily assist ICE. “An executive order can’t override a federal law,” he noted.

The policing executive order also includes a promise of legal support for officers who face lawsuits or financial liabilities for actions taken while on duty. The attorney general is directed to develop a system that may include pro bono legal aid from private firms, some of which have faced pressure from the administration in recent months.

In addition, the order calls for a review of all existing federal consent decrees—court-enforced agreements requiring police reforms—aiming to terminate those that “unduly hinder law enforcement operations.”

These consent decrees were widely used by the Obama Justice Department to address misconduct in troubled police departments but fell out of favor during Trump’s first term. Even under the Biden administration, they were slow to return due to concerns about their complexity and burdensome nature.

Now, amid a wave of resignations from the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division, new investigations into police departments appear increasingly unlikely.

Juan Cuba, executive director of Sheriff Accountability Action, says the bigger picture is disturbing. “When you connect all the dots—pressuring sheriffs to partner with ICE, promising them legal cover if sued—it sends a clear signal. It’s going to encourage more bad actors,” he warned.